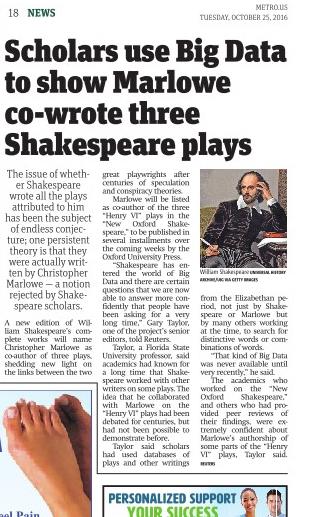

I have been asked many times, What is Digital Humanities? Here is a perfect example of how I could answer the question. I just read this in today’s Metro News.

I have been asked many times, What is Digital Humanities? Here is a perfect example of how I could answer the question. I just read this in today’s Metro News.

In this article , Kimon Keramidas offers a thorough definition by Jesper Juul of what a constitutes a game, as well as further expanding on the 6 characteristics which create this definition: rules, variable/quantifiable outcome, value assigned to possible outcome, player effort, negotiable consequences. Instead of giving attention to how games may be integrated into the learning environment, this article chose as its focal point what educators might extract from game design to create more successful and dynamic learning experiences for their students.

While I find it an absolutely worthwhile endeavor to analyze how education may benefit from game design (and the new technologies they encompass), much of this article echoed many of the same ideas I’ve have heard in conversations about the necessity of student-centered pedagogies. This feeling was further reinforced in the conclusion where Keramidas uses a quote expressed by influential educator and philosopher John Dewey in 1938.

“A primary responsibility of educators is that they not only be aware of the general principle of the shaping of actual experience by environing conditions, but also that they recognize in the concrete what surroundings are conducive to having experiences that lead to growth. Above all, they should utilize the surroundings, physical and social, that exist so as to extract from all that they have to contribute to building up experiences that are worth while.” – John Dewey

Hi everyone, wanted to share an article I just read that seems very germane to this week’s conversation on technology, games, and agency in learning. Thought-provoking piece that discusses some of the bigger players at the interstices of academia and user experience design: https://www.1843magazine.com/features/the-scientists-who-make-apps-addictive.

Neoliberalism believes that we have reached the end of history, a steady-state condition of free-market capitalism that will go on replicating itself forever.

The Neoliberal Arts, Willliam Deresiewicz

Freedom is acquired by conquest, not by gift. It must be pursued constantly and responsibly. Freedom is not an ideal located outside of man; nor is it an idea which becomes myth. It is rather the indispensable condition for the quest for human completion.

The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire

My provocation of Deresiewicz’s essay concerns the concept he puts forth of the role of youth in the age of neoliberalism. The role of youth in the neoliberal age, he argues, is different from what it was from the period of the romantics through modernity. Youth has historically been understood to inhabit the unique role of skeptical questioner of the world. Our current higher education system is skewing this expectation. With the mad rush to secure spots at perceived elite institutions for economic and philosophical reasons driven by post-modern neoliberal values, this historical role is being extinguished, with nothing unique or particularly notable to replace it. Young people are now simply small, less developed adults. But is this really true? And, what does this say about our concepts surrounding the role of adults in relation to their society?

Hi all,

If you are registered to attend the Game-Based Learning skills lab on Monday, October 24, please note the following:

The lab facilitator, Teresa Ober, asks that you bring your own laptop to the session, if possible. She would like to give you hands-on experience creating a game, which will require downloading and installing a (free) web app. The library computers in the lab space typically don’t allow students to do this, so it would be great if you had your own machine to work on.

Ian Bogost shines a dim light on the recent trend in product and service development around quantifying user experience, a trend he calls “exploitationware.” He begins his article by speaking about this trend by its more commonly used name, “gamification,” and focuses his argument on the “game” as well as the “-ify” qualifier added to it. I see issues with both aspects of his argument but will limit my provocation to just one: the linkage between gamification and games, and Bogost’s treatment of games as magical and powerful entities.

First, I’d like to point out that the type of exploitative behaviors that Bogost condemns in the implementation of gamification is widespread in game design itself. Studies have shown that many “free-to-play” games – a pricing model that rakes in millions despite the use of the term “free” – are structured around techniques employed by gambling services to entice their customer to spend as much money as possible over a long period of time via small impulsive payments that cumulatively grow beyond what the same customer might spend in a single large sum. Considering that many of these games are marketed towards children, I consider this the epitome of exploitation.

Second, while the terminology around gamification does include many game-related concepts such as points, I do not see games themselves as being the motivators of non-gaming industries adopting gamification techniques. Whether in the case of frequent flyer miles, the number of followers on your Instagram, or the leaderboards your smartwatch displays after every run, these services and products are not being “gamified” but, rather, are being made more interactive through the quantification of the level of interaction that the consumer engages in. These techniques exist in simple methods such as the card from the coffee shop that records — and rewards — my purchases and are not at all directly linked to games themselves. Games can avoid using those methods and are just as likely, if not more so, to be exploitationware when they don’t.

Hello everyone–

I just wanted you to know that this Saturday MOMA is hosting its second annual Arte y Cultura Latinoamericana (“WikiArte”) edit-a-thon starting at 10AM. For details, check the Wikipedia meetup page and/or the Facebook invite below. I will be there about 12-1pm as I have to grade papers in the morning…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Meetup/WikiArte/MoMA_2016

As I started to read the Introduction of the article, I asked myself when was Errors and expectations written? I was taken by surprise when I saw 1979 and not a year closer to 2016. Upon reading the following, in some, the numbers were token: in others, where comprehensive policies of admissions were adopted, the number threatened to ‘tip’ freshman classes in favor of the less prepared students. Four such colleges, this venture into mass education usually began abruptly, amidst the misgivings of administrators, who had to guess in the dark about the sorts of programs they ought to plan for the students they had never met, I felt that although 37 years have passed since these words were written, they are so true today. Administrators are making decisions that from a pedagogical perspective do not make sense. I would love to continue with examples, but there would be so many and we need to make short provocation points.

As I continued to read, it was totally amazing how I could relate to the problems that Mina was writing about in 1979 to problems in 2016 in the admitting process. Accept as many numbers possible and we will try to fix them later so that they can catch up philosophy. It reminded me of a comment I heard at a Departmental meeting once, basically, “just make it work.” I was taken back because I had not met my student’s yet, and was concerned as the type of student I would be having in my classroom and that I would have to make adjustments because I had to make the situation work without question.

Mina spoke about the importance the teacher’s for the success or failure of these young adults whom arrive to their Freshman year of college with many errors and it is teacher who is confronted by what appears to be a hopeless tangle of errors and inadequacies, must learn to see below the surface of these failures the intelligence and linguistic aptitudes of his students. And in doing so, he will himself become a critic of his profession and begin to search for wiser, more efficient ways of teaching young men and women to write.

Writing assignments have always caused me many struggles, not only as a student but also as a teacher. Personally, I had to learn how to write academically in English and Spanish (two completely different worlds), so I am aware of the challenge when I am assigning and responding to my students’ writing.

I find that students enrolled in language classes benefit greatly from low stakes writing; having a blog for the class where students contribute on a weekly basis with their ideas and thoughts about many and different topics covered in class (identity, language, ethnicity, etc.) allows them to freely participate and get actively involved. However, I think that the high stake writings are more challenging. I find it useful to elaborate the rubrics as a whole class and assign two drafts before the final version is due. How many drafts do your students submit before the final version? What techniques do you use to improve your students’ writing? On the other hand, I have attended several workshops and read about peer feedback in class. What do you think about it? Does it work with your students? I have tried to integrate it into my class several times but I have not been successful.

Language classes, as many other subjects, are a requirement for College students in which grammar based pedagogy does not have room for critical thinking. Students’ expectations and department policies restrain instructors and adjuncts to use different methodologies – a final common exam must be distributed to all the sections. What can we do to improve our students’ learning experience?

It’s an understatement to state that the opening chapters of Freire’s Pedagogy of the oppressed resonated with me on multiple intersecting levels; a reflection of my own philosophical underpinnings and life experience growing up in a working poor family in Newark, NJ, as a long-time organizer of low-wage workers and presently as a non-traditional doctoral student with aspirations to engage in critical “big-picture” labor and working class education – like many others with ambitions to foster “critical reflection” as the basis for praxis, “reflection and action upon the world in order to change it.” (51) It is difficult to hone in on just a few points about a treatise as essential as Freire’s but here are some observations from my standpoint both as a long-term organizer and experience and aspirations as an educator within labor and social movements and in the academy.

Freire delineates the painstaking process through which the oppressed may overcome norms and structures of dehumanization and attain genuine agency; for the oppressed to be able to “wage the struggle for their liberation, they must perceive the reality of oppression not as a closed world from which there is no exit, but as a limiting situation which they can transform” (49) Making this consciousness-raising (conscientizacao) possible requires overcoming internal and external obstacles faced by the oppressed. Internal obstacles include their own self-depreciation, humility and fatalism, the tendency to assume the interests of their oppressors as their own and to compete with rather than join together with others of the oppressed in the effort to elevate their own status. At the same time as the oppressed may fatalistically accept and blame themselves for their own lot, for the oppressors, “having more is an inalienable right, a right they acquired through their own “effort,” with their “courage to take risks.” (59) And as Freire observes even those of the “oppressor” class that seek to stand on the side of justice often adopt an approach more of charity than solidarity – believing themselves better situated to assume leadership rather than trusting the ability of oppressed peoples to possess knowledge, engage in critical reflection and take ownership over their own movements.

Anybody that has spent any time organizing understands these barriers as well as the capacity of people to transcend them. Freire draws out these processes and the necessity of employing a humanizing pedagogy constructed upon critical reflection, experiential knowledge, and the engaged action of the oppressed as the only means of undoing systems of oppression and making humanization possible. “It is only when the oppressed find the oppressor out and become involved in the organized struggle for their liberation that they begin to believe in themselves. This discovery cannot be purely intellectual but must involve action; nor can it be limited to mere activism, but must include serious reflection: only then will it be a praxis. Critical and liberating dialogue, which presupposes action, must be carried on with the oppressed at whatever the stage of their struggle for liberation.” (65)